What is Blackout Poetry?

Every day readers are bombarded with everything from tweets to text messages to ebooks to articles from The Onion. There is so much that it is impossible to read it all Writing professor and author Kenneth Goldsmith once declared in an essay that “The world is full of texts, more or less interesting; but I do not wish to add any more.” He proposes that because the world is already so filled within this ocean of texts that writers should not produce more but rather “learn to negotiate the vast quantity that exists.” Poets, however, have already been tackling this negotiation in a variety of ways for a long while. There is so much that it is impossible to read it all.

Writing professor and author Kenneth Goldsmith once declared, “The world is full of texts, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add any more.” Instead, he proposes that because the world is already so filled with all of these texts that writers should not produce more but rather “learn to negotiate the vast quantity that exists.” It is how we process all of these texts, according to Goldsmith, that “distinguishes my writing from yours.”

Over the past century, poets have gotten rather good at this navigation and separating themselves from others via their unique methods. Annie Dillard, for instance, erases, while Jonathan Safran Foer cuts out words, leaving some dangling, just barely still attached to the page. Mary Ruefle uses white out to cover words. Tristian Tzara pulls the words of newspaper articles out of a bag on stage and arranges them in front of an audience. Jen Bervin stitches over sentences with a needle and thread. Tom Phillips paints over the same pages of a Victorian novel again and again. Drew Myron adds line breaks to and rearranges the instructions of medical bottles. Even though these methods are all a little different, they are all a part of the same subgenre of poetry: found poetry.

Dillard describes this found poetry as “pawing through popular culture like sculptors on trash heaps…[poets] hold and wave aloft usable artifacts and fragments: jingles and ad copy, menus and broadcasts.” These found poets take texts and change them in some way, creating something akin to “the literary version of a collage.” We know through the aforementioned examples (and those represented are only the tiniest fraction of ways found poets are creating), that there are many ways to create these kinds of poems; however, we can identify several common methodologies and thus categories of found poetry.

Found Poetry Review, one of the few magazines that publishes only found poems, identifies four categories: erasure (poems created through erasing parts of a source text and leaving others behind), cento (combining lines from other works into a new poem), cut-up (physically cutting up a source text and rearranging its pieces into a new piece) and free-form excerpting and remixing (excerpting words and phrases from source text(s) and arranging them to create something new). Though Found Poetry Review, and many other publications list. only these four categories, there is an additional fifth that is often lumped into erasure poetry: blackout poetry.

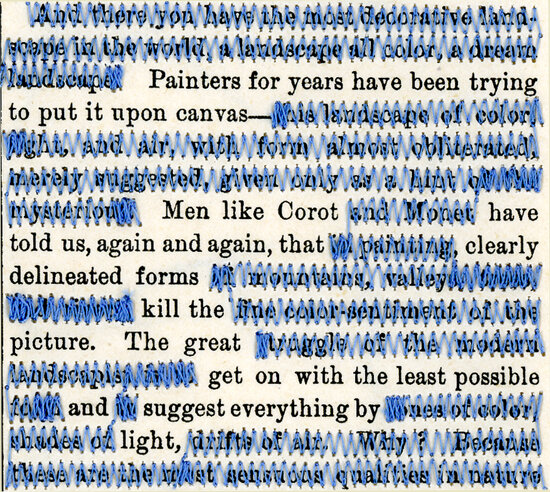

Blackout poetry refers to any poem in which the author covers a majority of a source text in favor of leaving a handful of words exposed to form a poem. There are many ways to cover the preexisting text. Poets paint, collage, scribble with pen and pencil and crayon over pages of books and newspapers and all kinds of other texts. Even though there is variation in the how, they all do the same thing, which is obscure the source text but never remove it.

Most current literature conflates blackout and erasure poems as the same thing, even Found Poetry Review, which defines erasure poetry as when “Poets take an existing source (usually limited to one or a few pages) and erase the majority of the text, leaving behind select words and phrases that, when read in order, compose the poem. Examples include Tom Phillips’ A Humument, (1970) Jen Bervin’s Nets (2004), and Austin Kleon’s Newspaper Blackouts (2010), just to name a few.” While their definition is correct, all the examples Found Poetry Review lists are not erasure poems. They are actually blackout poems.

Even blackout poets often misidentify their own work and refer to it as erasure over blackout poetry. In 2018, for example, blackout poet Isobel O’Hare published all this can be yours (2018), a collection of blackout poems made from the apology statements of sexual abusers during the #MeToo movement. In the introduction of the collection, however, they refer to the poems as erasures. They say, “I just really wanted to erase their words. So I grabbed a sharpie and went to work.” While O’Hare here is obscuring, altering, and manipulating these abusers’ words, I argue they do not erase them. The words are still there, just covered by sharpie.

This kind of misidentification is common, and it has led to the marginalization of blackout poetry as an independent category of found poetry and has contributed to a misunderstanding of what both erasure and blackout poetry are. Many assume that they are the same thing because we use these words interchangeably to refer to poems. However, they are not the same thing at all.

Isobel O’Hare’s poem “women attacking me” made from Russell Simmon’s statement and shared on Twitter November 23, 2017.

Erasure poet M. NourbeSe Philip explores this conflation in the end notes of her erasure project Zong! (2011). She asks “I white out and black out works (is there a difference?).” In answer to her question, I pose another by Andrew Allport: “So how to make art? With pen or knife?” In her poetry, Philip cuts out the words from her source text in order to make a poem that features a few lingering black words harsh against a mostly empty white page. Comparably, blackout poets like Austin Kleon, Tom Phillips, and O’Hare do not use a knife to disfigure their source texts but rather a pen (or in Phillips’s case everything from a pen to a paintbrush to collaged photographs) to cover them. Erasure poems depend on subtraction, whereas blackout poems depend on addition. This difference in methodology leads to an aesthetically different final product from erasure.

Erasure poet John Nyman suggests that “to erase means to ‘scrape out’ not merely partition or to cover up, and so an erasure indicates something that is no longer intact, complete, or available as such.” This removal implies both irreversibility and violence, as one cannot “scrape in” or “unscrape” the words that were taken out. Instead, the source text’s words are permanently excised from the poem. In fact, erasure poets sometimes go so far as to restructure the poem so that it does not even resemble the source text’s form. Nothing lingers behind as it does in blackout poems.

Where erasure relies on subtraction, blackout poetry depends on addition. Blackout poet Mary Ruefele describes blackout as “bandaging the words, and the ones left were those that seeped out.” It is all dependent on what the poet adds and what they allow to seep through those blackouts. Take, for example, Tom Philips’ A Humument, which many credit as being one of the first, if not the first major blackout poetry project. To create A Humument, Phillips “treated” each page of the Victorian novel A Human Document by W. H. Mallock. When he first began treating the book, Phillips said, “I merely scored out unwanted words with ink leaving some (often too many) to stand and the rest more or less readable beneath rapidograph hatching.” Yet as he continued, his methods began changing as he began interacting with the source text in new ways, even adding paint, marker, and a photo of Mallock’s grave to the pages. When he reached the last page, he started anew and began treating the pages again, creating six distinct editions of A Humument. Critics such as Gwen Le Cor have described the book as “an ongoing layering and composition project” rather than just a collection of poems or a novel because of how Phillips has worked so intensely modifying the source text. Just as Le Cor stated, he added layer after layer of these things, but he never subtracted. The book’s original words always remained there, just under the surface. It is all this layering over and covering up that makes his work unique. People read this book because of what he adds to it. They buy each edition because they want to see he has added more to Mallock’s original writing.

Had Phillips simply erased the words on each page except the ones he wanted, the book would not look the same at all. Blackout poems often resemble their source text and maintain the source text’s original structure to an extent. Erasure poems, however, require poets to more permanently modify a text. As Nyman suggested, they scrape out a handful of words from the source text, and in doing so often eliminate the text’s original structure in favor of moving the remaining words around. Some erasure poets maintain the words’ placement on the page as they were first published, but by removing the rest, we lose sense of the composition of the original page. It would not be the version of A Humument that so many people have come to love. Poets can make an erasure poem and a blackout poem from the same words, but their final product would look completely different.

Look at, for example, these editions of the first page of A Humument.

Even over two editions, Phillips has maintained Mallock’s general structure for the opening page with the title and then a line followed by a subtitle and then a block of text. We read the page knowing it is a page of something else, even pulling on the context of the faded “Introduction” behind the red colored pencil. Comparably, if he had erased everything, the final product of this page might look something like this:

In dropping these words on the page without that structure, the poem changes. The words are no longer grouped together in four separate little stanzas. Nor do we get the sense of repetition from the title of Phillip’s book standing over the title of the source text that is partially obscured by “New Edition.” In Phillips’s version, it is suggested this has happened before but now that Phillips’s song has come again to show us new things he has hidden and also revealed. We are encouraged to listen to this song through him telling us “now read on.” But the erasure version of that loses so much of this meaning through the structural changes. We just read it straight down the line.

The erasure version I have made also lacks Phillips’ hand drawn imagery, specifically the arrow that tells us readers to move on through the book. Our eyes follow it from the dark to the light, eager to turn the page, while the erasure poem gives none of that same urgency to move forward. Blackout poets have the ability to add additional meaning to their poems by adding visuals that erasure poems cannot. For instance, take these pieces created by teen poets for The New York Times blackout poetry contest in 2019. In “Stars,” Jewel Guerra places her poem about space within a physical representation of space. Her words become physically buried amongst “the tombstones of Earth” she refers to in her poem.

“Stars” by Jewel Guerra

“Triggers” by Brianne Kunisch

Additionally, in “Triggers” Brianne Kunisch writes about the fear of school shootings. She incorporates a gun at the bottom of the piece that looks almost as if the poem is trying to defend the reader from the gun. These visual aspects add to these pieces, as they are no longer communicating solely with an alphabetic language. They have added and intermixed a visual language to their initial alphabetic one.

Additionally, these aesthetic differences also carry different political connotations. For erasure poetry, that connotation is violence. It is inherent even in the history of the word itself. In her oft-quoted essay, “The Near Transitive Properties of the Political and Poetical Erasure,” poet Solmaz Sharif states, “Erasure means obliteration. The Latin root of obliteration (ob- against and lit(t)era letter) means the striking out of text.” This idea of striking out is a violent, one charged with physical harm. Thus to enact erasure onto a text, we have to do harm to it.

It is in this violence that we can find a further violent political connotation. In order to do harm to a text, to strike it out, we must have some kind of power over it. Nyman refers to creating erasure poems as “the application—often violent, but always forceful—of power or agency.” This is reminiscent of how oppressors have long utilized their power order to violently erase what would encourage those they wanted to control to stand up to them. Erasure is, as Jennifer Cheng calls it “a historical tool of the oppressor.” As such, the word erasure and the act of erasing both carry a specific connotation of violence that informs the meaning and creation of erasure poems.

I cannot fully speak to what it is like to experience erasure due to my privilege as a white cis-passing individual who has not had to experience erasure based on my identities, but there are poets, particularly poets of color, who can speak to this more so than I. For instance, we can look at the erasures of Craig Santos Perez, who has experienced significant erasure of his culture, community and even language by the United States as a Chamoru from the Pacific Island of Guåhan. Because the U.S. has so radically attempted to destroy his world through erasure, Perez suggests in his essay “from A Poetics of Continuous Presence and Erasure” that he finds himself writing “from a continuous space of erasure” because of the U.S.’s actions. He cannot escape the impacts of erasure even still today, which only speaks to the long lasting violence of erasure.

Furthermore, it is significant for us to consider this political connotation because poets from oppressed communities and backgrounds have begun using erasure as a tool to erase the words of their oppressors in order to tell the stories those very same oppressors once tried to obliterate. Cheng touches on this in her essay series on qualities of erasure poetry, suggesting “erasure’s refractive qualities are used by artists and poets to reclaim language, to retell dominant and oppressive narratives, to expose historical erasures, or in some cases even to repay violence to violent texts.” Perez is doing just what Cheng is describing by writing erasure poems to tell the story of the erasure of his culture and people. He uses erasure from a place of erasure in order to speak out against those who attempted to erase them and bring attention to his own erasure.

In a 2015 interview, Perez even remarked that he includes purposefully. He says, “Erasure is ever-present in my work in the sense that it's the silencing that I am always writing against. I try to dramatize that erasure in various ways, including with strikethroughs, blank space, font color, and narrative gaps/absences.” It is the political connotation of erasure that has caused Perez to write erasure poetry. Without that connotation, he likely would not have chosen to write these kinds of poems.

Because of this connotation with the oppression and erasure of people, communities, and culture, erasure poetry cannot be separated from historical violence. To do so would be disingenuous to the genre and to the history it carries. Cheng ponders this asking, “Perhaps [erasure] is always inherently a political act. Perhaps it is always inherently a violent act, the removal of language as either defacing or disremembering. If erasure is a historical tool of the oppressor, can it ever be artistically innocent?” When readers engage with erasure poems, they are engaging with that history and violence even if they are not consciously aware of it.

Because blackout poetry often prevents the source text’s words from being fully read, some scholars and poets have conflated the political differences between blackout and erasure just as they have conflated their names. For instance, in her essay, Sharif refers to blackout poetry as erasure and connecting it to the United States government redacting information. Erasure poet Srikanth Reddy also conflates erasure and government redaction in describing his process: “I then deleted language from the book, like a government censor blacking out words in a letter from an internal dissident.” However, neither blackout poems nor government redaction fully erase any language. Sharif describes one of the goals of government redaction to “Render information illegible to make the reader aware of his/her position as one who will never access a truth that does, by state accounts exist.” Blackout poems and government redactions purposefully create illegibility, obscuring portions of texts purposefully. However, according to Sharif, blackout poems “highlight via illegibility” by pulling out words to be read. Government redaction, on the other hand, covers words to prevent them from being read.

Erasure poets erase. That cannot be refuted. They obliterate others’ words in order to morph a source text into something that has a new meaning. As such, erasure poems cannot disengage from the political connotation of erasure. However, blackout poetry is not analogous with government redaction in the same way due to this highlighting. Nor does it violently erase and destroy like erasure poetry. Instead it carries the implication of censorship, perhaps even temporary censorship as those lines could theoretically be removed and the original words would still be there.

As readers, critics and even poets ourselves, we must acknowledge these differences in methodology, aesthetics and political connotation. Erasure and blackout poems are two markedly different categories of poetry and the conflation of the two has caused us to ignore the significance and impact of these categories on the writing world, politics, education and even popular culture.

I hope to help separate blackout from erasure in order to encourage us to stop conflating the two and instead critically consider how their differences shape how we engage with both blackout and erasure works separately as individuals and a community. Through this project, I have traced the contemporary history of blackout poetry, including its conflation with erasure, in order to help us define what blackout poetry is and is not.

Each page tackles a different movement, author, or impact of blackout poetry. However, the project is divided into four major categories. The first deals with what blackout poetry is while also introducing where it came from. The second touches on the academic coverage of this category of poetry. The third and fourth deal with the two major movements within blackout’s contemporary history: blackout as political commentary and resistance and the DIY-ing of blackout poetry.

Additionally, blackout and erasure poetry are communities as well as being categories of poetry. The below flow chart tracks some of the additional connections among different authors and works, including their inspirations, individuals they have worked with and even where they went to school in an attempt to help trace the contemporary evolution of blackout poetry. For example, one can trace how the Spiderweb Salon creative collective in Denton, TX is connected to popular blackout poet Isobel O’Hare who studied under Mary Ruefle at Vermont College of Fine Arts who was interviewed in The Kenyon Review by Andrew David King who attended the Iowa’s Young Writer’s Workshop, an extension of the Iowa’s Writer’s Workshop that erasure poet Srikanth Reddy graduated from. This chart hopes to show the connections between this community that may not be as obvious at first but that did impact the growth of these communities and categories of poetry. It is not meant to serve as a comprehensive list of all connections but rather serve as a starting point for researchers. As the blackout poetry and the scholarship continues to grow in popularity as will this site and flow chart.