DIY: Moving Blackout Poetry Into the Hands of The Reader

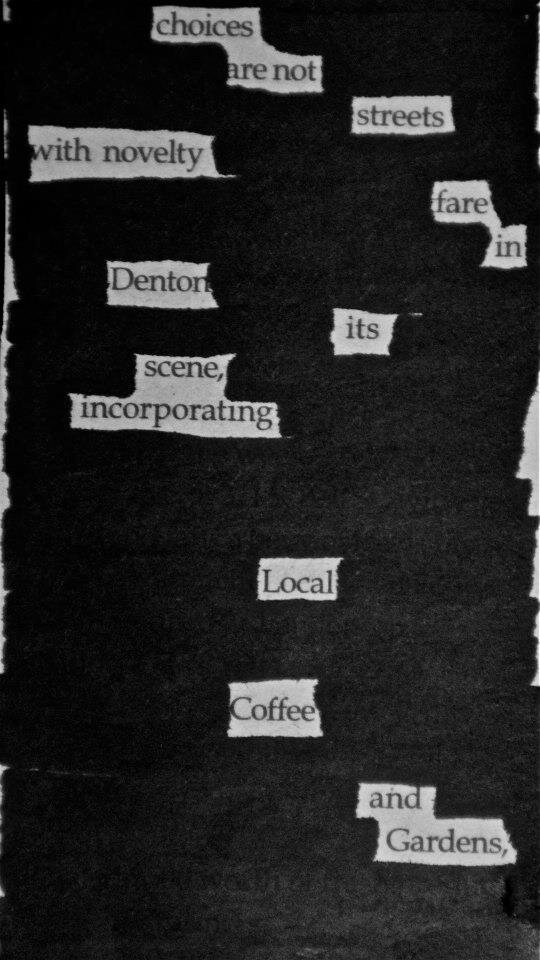

Visitors to a blackout poetry show creating their own blackout poems in Denton, TX.

Many of the movements that led up to blackout poetry, such as L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry, Oulipo, and conceptual poetry, I had never heard of before starting a creative writing program. Most of my friends had not heard of them either, but they had all heard of blackout poetry. In fact, most people in my life from my parents to my coworkers have some idea of what blackout poetry is even if they, like me, cannot place where they first learned about it. This is because since the 2010s, blackout poetry has increasingly left more experimental creative writing programs like Vermont College of Fine Arts and into the hands of the public.

This is due in part to what could be called the DIY-ing of blackout poetry. DIY or “do it yourself” refers to “activities in which individuals engage raw and semi-raw materials and component parts to produce, transform, or reconstruct material possessions, including those drawn from the natural environment” according to Marco Wolf and Shaun McQuitty. A simpler way to state this may be that it is anything that we do ourselves that we might pay someone else to do. In Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture (2014), Stephen Duncombe asserts that alongside this shift to making things ourselves, there arose a “DIY ethic” that called for people to “make your own culture and stop consuming that which is made for you.” Poetry, particularly more experimental forms of poetry like blackout and erasure, were once done by a more select group of people, those that had the time, leisure, and money to write and experiment freely. However, this shift toward DIY in the public sphere influenced those in the poetic. The everyday reader began to feel empowered to embrace this DIY ethic and begin both making their own blackout poems and teaching others how to make them.

There are thousands of blackout poetry how-to guides on the Internet. Once people start making blackout poems, they tend to find they need to share this with others. For instance, popular Instagram tarot card reader Carrie Mallon, who does not even call herself a poet, started making blackout poems in 2018 after being inspired by the Instagram account “@makeblackoutpoetry.” She found making blackout poetry to be “a psyche-healing activity” so she began sharing her poems on her own Instagram, which she uses to perform tarot readings and encourage self-discovery and healing. Her followers, who followed her for those readings not poetry, began asking her for advice on making them after she started posting them to her account. According to her blog, this made her “really excited because creating blackout poetry has really ‘clicked’ something within me, and I’d love to see others have that magical experience.” So she made her own “how to guide” after only a month of creating blackout poems.

Mallon’s experience is not unique. Wolf and McQuitty found in their study of those who undertake DIY projects that “DIY behavior can take on greater meaning than the functional or aesthetic value of the project. Study participants voiced feelings of accomplishment, control, and enjoyment when completing their projects.” People find real joy in making things themselves. In the art, music, and literature spheres, this goes even further. Wolf and McQuitty suggest that DIY in these spaces “involves consumers’ mental and physical engagement in acts of planning, designing, and fabricating for self consumption. By physically making things, a DIYer becomes the designer, builder, and evaluator of a project that is experientially consumed both during production and after its completion.” As she made her own poems, Mallon experienced these feelings of accomplishment and enjoyment both while making it and upon reading it when completed. This joy then made her feel as if she had to share this method with others.

Like Mallon, many of those who have been introduced to blackout poetry over the past ten years have begun sharing with their friends, family, and followers how to create blackout poems of their own. This has led to an enormous explosion of popularity for the form, a popularity that even exceeds that of erasure poetry. More people are now posting blackout poems online than erasure ones and have a better understanding as a result of what blackout poems are over what erasure poems are, which only furthers the need to separate the two categories.

A Brief Timeline of the Blackout Poetry DIY Movement

On Tik Tok, videos labeled with the hashtag “#blackoutpoetry” have been viewed over 700,000 times as of mid April 2020 and there are over 147,000 posts labeled with the same hashtag on Instagram. The DIY shift in the blackout poetry community has been primarily driven by an increase in the use of social media sites like Twitter, Instagram, and Tik Tok.

These platforms have become hotspots for blackout poetry, as they make it easy to share visual poems with strangers and to encourage those strangers to make their own. Several social media accounts have taken advantage of this by pushing for poets to share their work under a particular hashtag to participate in contests or publishing opportunities. For instance, the Instagram account “@makeblackoutpoetry” began by resharing any blackout poems posted under the hashtag “#makeblackoutpoetry.” Over 59,000 posts on Instagram have been tagged with the hashtag and the account has shared over 2,000 poems and generated a following of over 60,000 people. The man behind the account, John Carroll, went on to publish a book in 2018 titled Make Blackout Poetry: Turn These Pages Into Poems (2018) that teaches people how to create poems. However, he stopped posting to the account after the book came out. He last posted in February, 2019, over a year ago. Carroll is just one of many people who have used hashtags to promote this DIY mentality of blackout poetry.

Popular blackout poet Austin Kleon, for instance, also used hashtags to launch his career as a blackout poet. Unlike Carroll and a majority of social media based blackout poets, Kleon started by sharing his work on Tumblr where he encouraged people to submit blackout poems to his Tumblr for publication either via a form or by tagging it with the hashtag “#newspaperblackout.” While the blog went inactive in 2018, it gained significant attention while active, even being heralded as one of Time’s “30 Must-See Tumblr Blogs.” The attention he garnered digitally eventually led to a book deal and career of teaching people to make blackout poems and later just how to write in general.

Kleon set the standard for how to teach blackout poetry in community workshops; thereby, moving taking the DIY-ing of blackout poetry to another level. He was not just posting about online about how to make blackout poems, but he was interacting face-to-face with people, teaching them how to make this kind of poetry. He began hosting numerous workshops across Texas where he lives. Though he resides in Austin, he hosted a majority of his workshops in the DFW area, working primarily with the Dallas Museum of Arts (DMA) specifically. With the DMA, he had attendees create in the museum and then display their works in an exhibit as if they were famous pieces of artwork. On his blog, he recounts that he found that “folks really don’t need much instruction—they just need materials, some space, some time, and permission to play.” A few years after his DMA workshops, Kleon had his first solo art gallery showing about forty minutes north in Denton. At this gallery showing, he modeled his workshop and digital behaviors by encouraging visitors to create their own poems.

He made the focal point of the show a space for visitors to create. On his blog he recounted how “Much to my delight, visitors who attended the opening were already taking advantage—it’ll be great to see how those walls fill up over the next couple of weeks.” Kleon left the pieces visitors created up in the gallery for the duration of the show, thereby suggesting these visitors’ works had as much value as his own.

Kleon’s way of inviting people to create attracted others with similar mindsets and encouraged them to create and share their own blackout poems. For instance, courtney marie, poet and co-founder of Denton-based DIY creative collective Spiderweb Salon, created several blackout poems at Kleon’s show. Several of those went on to be published in We Denton Do It, alongside the blackout poems of other local poets and community members.

Blackout poem created by courtney marie at Austin Kleon’s Denton show and later published in We Denton Do It.

Spiderweb Salon and other similar DIY based creative communities such as the group responsible for The Found Poetry Review across the U.S. embraced blackout poetry. They began spreading blackout poetry amongst their local communities. For example, at zine making workshops, Spiderweb Salon frequently encourages and provides the materials for poets to create blackout poems. For instance, Sebastián Hasani Páramo, who studied under well known blackout poet Mary Ruefel at Sarah Lawerence College, created a blackout poem titled “Despair” from from Soren Kierkegaard’s The Sickness Unto Death (1849) for Spiderweb Salon’s zine Book of the Dead (2017). While Paramo has written a number of poems, he has not written much blackout poetry. The influence of Spiderweb Salon, however, appears to have encouraged him to experiment with this category of poetry.

Spiderweb Salon is additionally home to popular blackout poet Isobel O’Hare. Though O’Hare lives in New Mexico, they still participate in the collective’s various events and publications. In addition to their work with the collective, they also promote blackout poetry writers in their area and across the world. In 2018, they published a blackout poetry collection made from the apologies of sexual assaulters during the #MeToo movement entitled all this can be yours (2018). Their book quickly gained worldwide attention, and they have used that attention to empower writers to make their own blackout poems through local workshops and their community sourced anthology Erase the Patriarchy.

Like Kleon, they prioritized the voices of their readers through this project by encouraging them to become co-creators and make their own blackout poems. For the anthology, they asked for erasures (meaning both blackout and erasure poems) of “a statement, apology, speech, and/or other document, whether contemporary or historical.” While open to all submitters, the O’Hare stated that submissions from men would be accepted but that “preference will be given to women, non-binary, and LGBTQIA writers.” They started this project and prioritized these voices because “The best thing about making these erasures has been watching other people come up with their own, either of the same statements or of other documents written by men in powerful positions who have in some way abused that power. I thought, what better way to continue this project than to invite y’all along with me?” Poets like O’Hare and Kleon and groups like Spiderweb Salon began encouraging what Duncombe described as the DYI ethic of making a culture for yourself by creating a blackout poetry community and culture that empowers one another to use blackout poetry to share their stories and reclaim their voices.